Atlantis

Atlantis (Greek: ?£n£f£\£h£n?? £h?£m£j?, "Island of Atlas") is the name of

an island first mentioned and described by the classical Greek philosopher Plato.

According to him this island, lying "beyond the pillars of Hercules",

was a naval power, having conquered many parts of western Europe and Africa.

Soon after a failed invasion of Athens, Atlantis sank in the waves "in

a single day and night of misfortune" due to a natural catastrophe which

happened 9,000 years before Plato's time.

As a story embedded in Plato's dialogues, Atlantis is mostly seen as a myth

created by Plato to back up a previously invented theory with real facts. Some

scholars express the opinion that Plato intended to tell real history. Although

the function of the story of Atlantis seems to be clear to most scholars, they

dispute whether and how much Plato's account was inspired by older traditions.

Some scholars argue Plato drew upon memories of past events such as the Thera

eruption or the Trojan War, while others insist that he took inspiration of

contemporary events like the destruction of Helike in 373 BC or the failed Athenian

invasion of Sicily in 415¡V413 BC.

The possible existence of Atlantis was actively discussed throughout the classical

antiquity, but it was usually rejected and occasionally parodied. While basically

unknown during the Middle Ages, the story of Atlantis was rediscovered by Humanists

at the very beginning of modern times. Plato's description inspired the utopian

works of several Renaissance writers, like Francis Bacon's "New Atlantis".

To this day, Atlantis inspires today's literature, from science fiction to comic

books and movies.

Plato's account

Plato's account of Atlantis is written in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias,

dated circa 360 BC. These works contain the earliest known references to Atlantis.

The dialogue Critias was never completed by Plato for an unknown reason, however

scholar Benjamin Jowett among others, argues that Plato originally planned a

third dialogue titled Hermocrates. John V. Luce assumes that Plato ¡X after describing

the origin of the world and mankind in Timaeus as well as the allegorical perfect

society of ancient Athens and its successful defense against an antagonistic

Atlantis in Critias ¡X would have made the strategy of the Hellenic civilisation

during their conflict with the barbarians a subject of discussion in the phantom

dialog.

The four persons appearing in those two dialogues are the politicians Critias

and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus, although only

Critias speaks of Atlantis. While most likely all of these people actually lived,

these dialogues as recorded may have been the invention of Plato. In his written

works, Plato makes extensive use of the Socratic dialogues in order to discuss

contrary positions within the context of a supposition.

The Timaeus begins with an introduction, followed by an account of the creations

and structure of the universe and ancient civilizations. In the introduction,

Socrates muses about the perfect society, described in Plato's Republic, and

wonders if he and his guests might recollect a story which exemplifies such

a society. Critias mentions an allegedly historical tale that would make the

perfect example, and follows by describing Atlantis as is recorded in the Critias.

In his account, ancient Athens seems to represent the "perfect society"

and Atlantis its opponent, representing the very antithesis of the "perfect"

traits described in the Republic. Critias claims that his accounts of ancient

Athens and Atlantis stem from a visit to Egypt by the Athenian lawgiver Solon

in the 6th century BC. In Egypt, Solon met a priest of Sais, who translated

the history of ancient Athens and Atlantis, recorded on papyri in Egyptian hieroglyphs,

into Greek. According to Plutarch the priest was named Sonchis, but because

of the temporal distance between Plutarch and the alleged event, this identification

is unverified.

According to Critias, the Hellenic gods of old divided the land so that each

god might own a lot; Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed

the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Libya and Asia Minor combined,

but has since been sunk by an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal,

inhibiting travel between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. The

Egyptians described Atlantis as an island approximately 700 kilometres (435

mi) across, comprising mostly mountains in the northern portions and along the

shore, and encompassing a great plain of an oblong shape in the south "extending

in one direction three thousand stadia [about 600 km; 375 mi], but across the

center inland it was two thousand stadia [about 400 km; 250 mi]."

Fifty stadia inland from the coast was a "mountain not very high on any

side." Here lived a native woman with whom Poseidon fell in love and who

bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful

king of the entire island and the ocean (now the Atlantic Ocean), and was given

the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin

Gadeirus or Eumelus in Greek, was given the easternmost portion of the island.

The other four pairs of twins ¡X Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon,

Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes ¡X "were the inhabitants and

rulers of divers islands in the open sea."

Poseidon carved the inland mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed

it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three

stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then

built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the

island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved

tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around

the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage

to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each of the

city's rings. The walls were constructed of red, white and black rock quarried

from the moats, and were covered with brass, tin and orichalcum, respectively.

According to Critias, 9,000 years before his lifetime a war took place between

those outside the Pillars of Hercules- commonly considered to be the Strait

of Gibraltar- and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered

the Mediterranean as far east as Egypt and the continent into Tyrrhenia, and

subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors

against the Atlantean empire and as the alliance disintegrated, prevailed alone

against the empire, liberating the occupied lands. "But afterwards there

occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune

all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis

in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea."

Receptions

Ancient

Other than Plato's Timaeus and Critias there is no primary

ancient account of Atlantis, which means every other account on Atlantis relies

on Plato in one way or another. To this day, no proof for a non-Platonic tradition

of Atlantis has been found. However, the Greek logographer Hellanicus of Lesbos

wrote a work (now lost), named Atlantis (or Atlantias), about the daughters

of the titan Atlas (not the Atlas mentioned by Plato). However, it is unlikely

that this work was an inspiration to Plato, since he named Atlantis after the

Atlantic Ocean (ancient Greek: ?£n£f£\£h£n?? £c?£f£\£m£m£\, "Sea of Atlas"),

which already had this name in the time of Herodotus.

Many ancient philosophers viewed Atlantis as fiction. The most popular might

be Aristotle, who is allegedly quoted by Strabo with the above mentioned commentary

on Atlantis.

However, in antiquity, there were also philosophers, geographers, and historians

who believed that Atlantis was real.For instance, the philosopher Crantor, a

student of Plato's student Xenocrates, tried to find proof of Atlantis' existence.

His work, a comment on Plato's Timaeus, is lost, but another ancient historian,

Proclus, reports that Crantor traveled to Egypt and actually found columns with

the history of Atlantis written in hieroglyphic characters. However, Plato did

not write that Solon saw the Atlantis story on a column but on a source that

can be "taken to hand". Proclus' proof appears implausible.

Another passage from Proclus' 5th century AD commentary on the Timaeus gives

a description of the geography of Atlantis: "That an island of such nature

and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated

the things around the outer sea. For according to them, there were seven islands

in that sea in their time, sacred to Persephone, and also three others of enormous

size, one of which was sacred to Pluto, another to Ammon, and another one between

them to Poseidon, the extent of which was a thousand stadia; and the inhabitants

of it¡Xthey add¡Xpreserved the remembrance from their ancestors of the immeasurably

large island of Atlantis which had really existed there and which for many ages

had reigned over all islands in the Atlantic sea and which itself had like-wise

been sacred to Poseidon. Now these things Marcellus has written in his Aethiopica".

However, Heinz-G Ênther Nesselrath argues that this Marcellus ¡X who is otherwise

unknown ¡X is probably not a historian but a novelist.

Other ancient historians and philosophers believing in the existence of Atlantis

were Strabo and Posidonius (cf. Strabo 2,3,6).

Plato's account of Atlantis may have also inspired parodic imitation: writing

only a few decades after the Timaeus and Critias, the historian Theopompus of

Chios wrote of a land beyond the ocean known as Meropis. This description was

included in Book 8 of his voluminous Philippica, which contains a dialogue between

King Midas and Silenus, a companion of Dionysus. Silenus describes the Meropids,

a race of men who grow to twice normal size, and inhabit two cities on the island

of Meropis: Eusebes (£H?£m£`£]??, "Pious-town") and Machimos (£O?£q£d£g£j?,

"Fighting-town"). He also reports that an army of ten million soldiers

crossed the ocean to conquer Hyperborea, but abandoned this proposal when they

realized that the Hyperboreans were the luckiest people on earth. Heinz-G Ênther

Nesselrath has argued that these and other details of Silenus' story are meant

as imitation and exaggeration of the Atlantis story, for the purpose of exposing

Plato's ideas to ridicule.

Somewhat similar is the story of Panchaea, written by philosopher Euhemerus.

It mentions a perfect society on an island in the Indian Ocean. Zoticus, a Neoplatonist

philosopher of the 3rd century AD, wrote an epic poem based on Plato's account

of Atlantis.

The 4th century AD historian Ammianus Marcellinus, relying on a lost work by

Timagenes, a historian writing in the 1st century BC, writes that the Druids

of Gaul said that part of the inhabitants of Gaul had migrated there from distant

islands. Ammianus' testimony has been understood by some as a claim that when

Atlantis sunk into the sea, its inhabitants fled to western Europe; but Ammianus

in fact says that ¡§the Drasidae (Druids) recall that a part of the population

is indigenous but others also migrated in from islands and lands beyond the

Rhine" (Res Gestae 15.9), an indication that the immigrants came to Gaul

from the north and east, not from the Atlantic Ocean.

Modern

Francis Bacon's 1627 novel The New Atlantis describes a utopian society, called

Bensalem, located off the western coast of America. A character in the novel

gives a history of Atlantis that is similar to Plato's, and places Atlantis

in America. It is not clear whether Bacon means North or South America.

In middle and late 19th century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars, starting

with Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and including Edward Herbert Thompson

and Augustus Le Plongeon proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to Mayan

and Aztec culture.

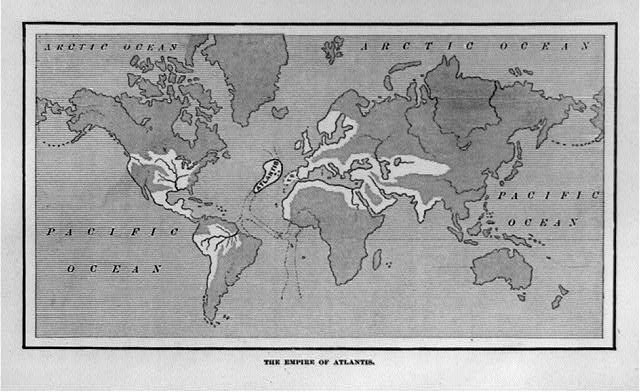

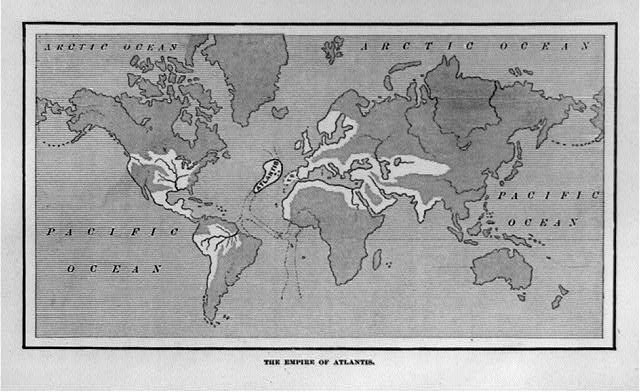

The 1882 publication of Atlantis: the Antediluvian World by Ignatius Donnelly

stimulated much popular interest in Atlantis. Donnelly took Plato's account

of Atlantis seriously and attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations

were descended from its high neolithic culture.

During the late 19th century, ideas about the legendary nature of Atlantis were

combined with stories of other lost continents such as Mu and Lemuria by popular

figures in the occult and the growing new age phenomenon. Helena Blavatsky,

the "Grandmother of the New Age movement," writes in The Secret Doctrine

that the Atlanteans were cultural heroes (contrary to Plato who describes them

mainly as a military threat), and are the fourth "Root Race", succeeded

by the "Aryan race". Rudolf Steiner wrote of the cultural evolution

of Mu or Atlantis. Famed psychic Edgar Cayce first mentioned Atlantis in a life

reading given in 1923, and later gave its geographical location as the Caribbean,

and proposed that Atlantis was an ancient, now-submerged, highly-evolved civilization

which had ships and aircraft powered by a mysterious form of energy crystal.

He also predicted that parts of Atlantis would rise in 1968 or 1969. The Bimini

Road, a submarine geological formation just off North Bimini Island, discovered

in 1968, has been claimed by some to be evidence of the lost civilization (among

many other things) and is still being explored today.

Before the time of Eratosthenes about 250 BC, Greek writers located the Pillars

of Hercules on the Strait of Sicily. This changed with Alexander the Great¡¦s

eastward expansion and the Pillars were moved by Eratosthenes to Gibraltar.

This evidence has been cited in some Atlantis theories, notably in Sergio Frau's

work. His theory, supported by scholars and archaeologists, is still studied

by the UNESCO.

A map showing a supposed location of Atlantis. From Ignatius Donnelly's Atlantis: the Antediluvian World, 1882.

Nationalist and Socialist ideas of Atlantis

Plato's Atlantis has been considered by some socialists as an early socialist

utopia. British nationalists identified the British isles with Atlantis.

The concept of Atlantis also attracted National Socialist (Nazi) theorists.

In 1938, Heinrich Himmler organized a search in Tibet to find a remnant of the

white Atlanteans. According to Julius Evola (Revolt Against the Modern World,

1934), the Atlanteans were Hyperboreans -- Nordic supermen who originated on

the North pole (see Thule). Similarly, Alfred Rosenberg (The Myth of the Twentieth

Century, 1930) spoke of a "Nordic-Atlantean" or "Aryan-Nordic"

master race.

Aleister Crowley has also written an esoteric history of Atlantis, although

this may be intended more as metaphor than as fact.

Recent times

As continental drift became more widely accepted during the 1950s, most "Lost

Continent" theories of Atlantis began to wane in popularity. In response,

some recent theories propose that elements of Plato's story were derived from

earlier myths.

Plato scholar Dr Julia Annas (Regents Professor of Philosophy, University of

Arizona) has had this to say on the matter:

"The continuing industry of discovering Atlantis illustrates the dangers

of reading Plato. For he is clearly using what has become a standard device

of fiction - stressing the historicity of an event (and the discovery of hitherto

unknown authorities) as an indication that what follows is fiction. The idea

is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power.

We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off

exploring the sea bed. The continuing misunderstanding of Plato as historian

here enables us to see why his distrust of imaginative writing is sometimes

justified."sometimes justified."[16]